Chapter 8: Psyche's Tasks

In addressing Venus, Psyche is going to the source of Cupid’s problems. Venus is antagonistic but also offers redemption, because she recognizes that Psyche is pregnant. She can’t have it be said she didn’t have a generous nature. She gives Psyche tasks that a mere mortal could never do successfully. Venus of course has her servants rough her up a bit, as befitting such a slut who has seduced her darling boy (8a, Giulio Romano).

There will be 4 tasks in all--the 4 elements, of which the tale says Venus was the source. Similarly, Sophia is the source of the 4 elements in Gnosticism; and 4 is the number of completeness for Jung. The tasks are the means by which the soul may achieve mundificatio, i.e. purification (8b, Emblem 7 of the Rosarium).

There are analogies to the purification of metals in metallurgy and alchemy. In the Rosarium series, all 4 would be subsumed under the ablutio or cleansing of the prima materia, basic matter, to find the philosopher’s stone within.

The first task is to separate out 7 types of seeds that she’s had her servants mix together. She has to have it done by the next morning (8c, Perin del Vaga).

Psyche despairs while others go about their day as usual (8d, Klinger).

A kindly ant sees her plight and enlists her fellows to help (8e, Giulio Romano).

Perhaps Pan had something to do with this ant; and maybe Pan and Cupid are friends. Separating seeds: learning discrimination, which she did not have when confronted by her sisters. Intuitive discrimination, of the heart. The 7 types of grain suggest the separation of alchemy’s 7 metals. Element--earth

Venus is surprised and suspects some trick. Psyche must now gather a bushel of fleece from the golden rams of the Sun (8f, Giulio Romano). She goes there, but the rams seem too fierce. They jump high and dash quickly, butting heads with each other in an earth-shaking show of strength. It is of course the Golden fleece: Psyche wants to drown herself.

But in the stream a reed starts talking to her (slide 8g, Burne-Jones). Wait til night, it says, and then you can gather fleece sticking to the trees while the rams are asleep.

She gets the job done (8h, Burne-Jones, 1860’s).

The situation here is like that in which volatile metals such as Mercury were separated from their ore by metallurgists. The ore was heated in an oven, and the metal vaporized. It cooled in the air and solidified on tree-like structures that the metallurgist had put in the oven (8i, from De Re Metallica, the first book to describe the process, by Georg Bauer, a German physician, better known by his name in Latin, Georgius Agricola). The operative element here is fire.

What is the life-lesson of this task? I think it is to wait for the right time and then act quickly, festina lente, a popular motto both in the Renaissance and in ancient Rome. One depiction of that motto is a dolphin on a anchor (slide 8j), waiting along with speed--something sailors had to do, too, waiting to come in on the tide.

It is to wait for the right time, when one has decided what to do, as opposed to acting immediately. Waiting also gives one time to deliberate and so be sure that the course of action is sound. The golden fleece here could be interpreted as a reference to Sulphur, the earthly sun-material, i.e. Cupid—she is rescuing him. Perhaps he is helping her as well, through the various things that talk to her.

Venus of course is not satisfied, but assigns a third task (slide 8k, by British artist George Romney, 1780s). Psyche is to get water of the Styx from its exact midpoint, where it comes out of its underground course within the highest mountain as a waterfall, and then goes underground again to Hades.

Psyche goes to the mountain and cries to heaven for deliverance (8l, Klinger).

The water of the Styx flows in the form of a waterfall, falling far below on a sheer cliff, guarded by a three headed dragon (8m).

But Jupiter’s eagle hears her and knows that Jupiter owes Cupid a favor, for the way Cupid helped Jupiter get his cup-bearer Ganymede. The eagle takes the jar and easily fills it from the waterfall (8n).

The meaning? The Styx is both the highest and the lowest, the clearest spring and the most putrid swamp. Corpses float in it, and it smells of sulphur. It is both dragons and Cupid, sulphur in the earth and sulphurin the heavens. Chemically, it is corrosive, poisonous sulphur along with the healing sulphur of mineral springs. Psychologically it is depression and mania. The story seems to say: Experience both the ups and downs of spirit, but keep the perspective of the midpoint. The element is water.

Venus is surprised and as usual suspects trickery (slide 8o, Raphael).

This time Venus has a task Psyche cannot get someone else to do for her. She needs some of Persephone’s beauty. All the recent stress has made her use up her supply, to keep from getting wrinkles. So will Psyche please take her box to Persephone and bring it back full again?

Why should beauty be found in Hades, we might ask? What Venus wants is a beauty that survives the wear and tear of existence, a divinity within one that survives not just death but hell. Chemically, water from deep below the earth frequently is good for the skin, heaing acne and other sores, by virtue of the sulphur in it.

Psyche is again in despair. She finds a high tower and prepares to jump off it. But perhaps Cupid will help her by proxy (8p, above-door painting by Johann Heinrich Mayer, 1795).

Magically, the tower she seeks to jump off from speaks to her, telling her where to find openings in the earth that lead to the underground river and how to get there and back safely. She must take 2 pieces of bread to distract Cerberus, the 3 headed dog that guards the entrance, and 2 coins, to pay the ferryman Charon back and forth. She cannot give anything to any beggars she might meet, because then she would not get back. And she is not to open the box once Persephone has filled it. That would mean not only failure but death as well.

To get to Hades, Psyche must cross the black waters of the Styx: the fear of dying, or of going into one’s blackest interior, the part of oneself one does not see or wish to know (slides 8q, George Romney, 1780’s, and 8r, Erica Ronnback, about 2005).

This corresponds to the stage of putrefactio in alchemy, also imaged as rotting corpses in black water (8r, Emblem 6 of the Rosarium).

But if it is one’s own interior, then what one gets will be one’s own beauty, not another’s. Hence in von Gierke’s 2005 version, the box has the woman’s own things in it, her pearls and ribbon (8s, my repetition of an image we have already seen, 6f).

The pearls are especially Gnostic, in that in the Gnostic Hymn of the Pearl, the hero has to kill the dragon and get the pearl in its belly, which is the missing pearl from the king’s crown in heaven.

Refusing the corpse and the other beggars. Von Franz sees the advice here as to be unsentimental. But Psyche already showed that in giving her sisters’ fatal misinformation. Be focused, stay on track: the sops are for Cerberus, the coins for Charon, not anyone else, if one expects to get back. So she confronts the dog (8t, book illustration by Edward Durat, 1951).

Then she pays Charon the ferryman with one of the coins the tower told her to bring (8t, watercolor by Burne-Jones, 1865). She ignores the talking corpse next to the boat who implores her for a coin, that he might not float there forever.

Once in Hades, she gives the jar to Persephone (8u, Giulio Romano) who obligingly fills it and hands it back (8v, by Perin del Vaga, in the Christian version of Hades, for Pope Paul III).

And of course once she has crossed the Styx and is back on the surface, she can’t resist taking a little for herself (8w, by Pre-Raphaelite John William Waterhouse, 1903-4).

Von Franz says this is the typical women’s vanity, and Eve like impulsiveness. But Psyche's getting the beauty is her laying claim to her own divinity, a “transgression” that really isn’t, I think. In von Gierke, as we have seen, the box with the pearls and the red ribbon is clearly hers from before (but of course, she is Venus as well as Psyche); by the same token, to do a task is to make it yours.

Von Gierke’s box, which before we looked at for its phallic significance, now has its proper symbolic value, as a feminine container, as the Holy Grail is often seen. She is claiming the divine feminine.

At the same time, we must imagine that Cupid is participating in this trial as well. The divine feminine is his own contrasexual shadow, his unconscious deepest fear, that of being contained by another, as he once was by his mother (and at the same time, it is his deepest longing).

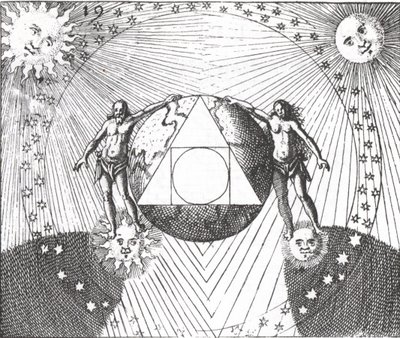

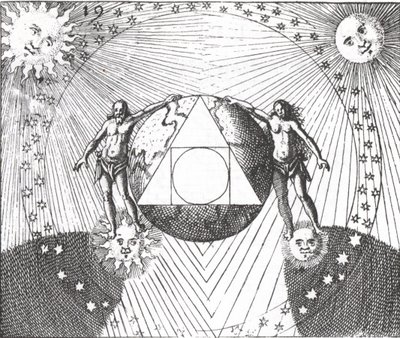

The box is his contrasexual shadow just as much as its reflective surface is hers. This double shadow is admirably portrayed in a complex alchemical image (8y, from the Philosophia Reformata of 1622) of which I can only point to one aspect. That the shadow of Sol has a little Luna which the king cannot see, and likewise for Luna. Moreover, since the male anima has an animus and vice versa, each is in each.

There will be 4 tasks in all--the 4 elements, of which the tale says Venus was the source. Similarly, Sophia is the source of the 4 elements in Gnosticism; and 4 is the number of completeness for Jung. The tasks are the means by which the soul may achieve mundificatio, i.e. purification (8b, Emblem 7 of the Rosarium).

There are analogies to the purification of metals in metallurgy and alchemy. In the Rosarium series, all 4 would be subsumed under the ablutio or cleansing of the prima materia, basic matter, to find the philosopher’s stone within.

The first task is to separate out 7 types of seeds that she’s had her servants mix together. She has to have it done by the next morning (8c, Perin del Vaga).

Psyche despairs while others go about their day as usual (8d, Klinger).

A kindly ant sees her plight and enlists her fellows to help (8e, Giulio Romano).

Perhaps Pan had something to do with this ant; and maybe Pan and Cupid are friends. Separating seeds: learning discrimination, which she did not have when confronted by her sisters. Intuitive discrimination, of the heart. The 7 types of grain suggest the separation of alchemy’s 7 metals. Element--earth

Venus is surprised and suspects some trick. Psyche must now gather a bushel of fleece from the golden rams of the Sun (8f, Giulio Romano). She goes there, but the rams seem too fierce. They jump high and dash quickly, butting heads with each other in an earth-shaking show of strength. It is of course the Golden fleece: Psyche wants to drown herself.

But in the stream a reed starts talking to her (slide 8g, Burne-Jones). Wait til night, it says, and then you can gather fleece sticking to the trees while the rams are asleep.

She gets the job done (8h, Burne-Jones, 1860’s).

The situation here is like that in which volatile metals such as Mercury were separated from their ore by metallurgists. The ore was heated in an oven, and the metal vaporized. It cooled in the air and solidified on tree-like structures that the metallurgist had put in the oven (8i, from De Re Metallica, the first book to describe the process, by Georg Bauer, a German physician, better known by his name in Latin, Georgius Agricola). The operative element here is fire.

What is the life-lesson of this task? I think it is to wait for the right time and then act quickly, festina lente, a popular motto both in the Renaissance and in ancient Rome. One depiction of that motto is a dolphin on a anchor (slide 8j), waiting along with speed--something sailors had to do, too, waiting to come in on the tide.

It is to wait for the right time, when one has decided what to do, as opposed to acting immediately. Waiting also gives one time to deliberate and so be sure that the course of action is sound. The golden fleece here could be interpreted as a reference to Sulphur, the earthly sun-material, i.e. Cupid—she is rescuing him. Perhaps he is helping her as well, through the various things that talk to her.

Venus of course is not satisfied, but assigns a third task (slide 8k, by British artist George Romney, 1780s). Psyche is to get water of the Styx from its exact midpoint, where it comes out of its underground course within the highest mountain as a waterfall, and then goes underground again to Hades.

Psyche goes to the mountain and cries to heaven for deliverance (8l, Klinger).

The water of the Styx flows in the form of a waterfall, falling far below on a sheer cliff, guarded by a three headed dragon (8m).

But Jupiter’s eagle hears her and knows that Jupiter owes Cupid a favor, for the way Cupid helped Jupiter get his cup-bearer Ganymede. The eagle takes the jar and easily fills it from the waterfall (8n).

The meaning? The Styx is both the highest and the lowest, the clearest spring and the most putrid swamp. Corpses float in it, and it smells of sulphur. It is both dragons and Cupid, sulphur in the earth and sulphurin the heavens. Chemically, it is corrosive, poisonous sulphur along with the healing sulphur of mineral springs. Psychologically it is depression and mania. The story seems to say: Experience both the ups and downs of spirit, but keep the perspective of the midpoint. The element is water.

Venus is surprised and as usual suspects trickery (slide 8o, Raphael).

This time Venus has a task Psyche cannot get someone else to do for her. She needs some of Persephone’s beauty. All the recent stress has made her use up her supply, to keep from getting wrinkles. So will Psyche please take her box to Persephone and bring it back full again?

Why should beauty be found in Hades, we might ask? What Venus wants is a beauty that survives the wear and tear of existence, a divinity within one that survives not just death but hell. Chemically, water from deep below the earth frequently is good for the skin, heaing acne and other sores, by virtue of the sulphur in it.

Psyche is again in despair. She finds a high tower and prepares to jump off it. But perhaps Cupid will help her by proxy (8p, above-door painting by Johann Heinrich Mayer, 1795).

Magically, the tower she seeks to jump off from speaks to her, telling her where to find openings in the earth that lead to the underground river and how to get there and back safely. She must take 2 pieces of bread to distract Cerberus, the 3 headed dog that guards the entrance, and 2 coins, to pay the ferryman Charon back and forth. She cannot give anything to any beggars she might meet, because then she would not get back. And she is not to open the box once Persephone has filled it. That would mean not only failure but death as well.

To get to Hades, Psyche must cross the black waters of the Styx: the fear of dying, or of going into one’s blackest interior, the part of oneself one does not see or wish to know (slides 8q, George Romney, 1780’s, and 8r, Erica Ronnback, about 2005).

This corresponds to the stage of putrefactio in alchemy, also imaged as rotting corpses in black water (8r, Emblem 6 of the Rosarium).

But if it is one’s own interior, then what one gets will be one’s own beauty, not another’s. Hence in von Gierke’s 2005 version, the box has the woman’s own things in it, her pearls and ribbon (8s, my repetition of an image we have already seen, 6f).

The pearls are especially Gnostic, in that in the Gnostic Hymn of the Pearl, the hero has to kill the dragon and get the pearl in its belly, which is the missing pearl from the king’s crown in heaven.

Refusing the corpse and the other beggars. Von Franz sees the advice here as to be unsentimental. But Psyche already showed that in giving her sisters’ fatal misinformation. Be focused, stay on track: the sops are for Cerberus, the coins for Charon, not anyone else, if one expects to get back. So she confronts the dog (8t, book illustration by Edward Durat, 1951).

Then she pays Charon the ferryman with one of the coins the tower told her to bring (8t, watercolor by Burne-Jones, 1865). She ignores the talking corpse next to the boat who implores her for a coin, that he might not float there forever.

Once in Hades, she gives the jar to Persephone (8u, Giulio Romano) who obligingly fills it and hands it back (8v, by Perin del Vaga, in the Christian version of Hades, for Pope Paul III).

And of course once she has crossed the Styx and is back on the surface, she can’t resist taking a little for herself (8w, by Pre-Raphaelite John William Waterhouse, 1903-4).

Von Franz says this is the typical women’s vanity, and Eve like impulsiveness. But Psyche's getting the beauty is her laying claim to her own divinity, a “transgression” that really isn’t, I think. In von Gierke, as we have seen, the box with the pearls and the red ribbon is clearly hers from before (but of course, she is Venus as well as Psyche); by the same token, to do a task is to make it yours.

Von Gierke’s box, which before we looked at for its phallic significance, now has its proper symbolic value, as a feminine container, as the Holy Grail is often seen. She is claiming the divine feminine.

At the same time, we must imagine that Cupid is participating in this trial as well. The divine feminine is his own contrasexual shadow, his unconscious deepest fear, that of being contained by another, as he once was by his mother (and at the same time, it is his deepest longing).

The box is his contrasexual shadow just as much as its reflective surface is hers. This double shadow is admirably portrayed in a complex alchemical image (8y, from the Philosophia Reformata of 1622) of which I can only point to one aspect. That the shadow of Sol has a little Luna which the king cannot see, and likewise for Luna. Moreover, since the male anima has an animus and vice versa, each is in each.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home