Chapter 6: Sisterly Advice

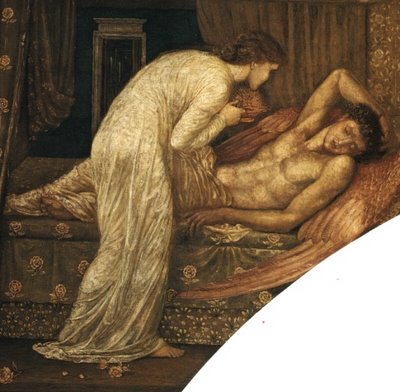

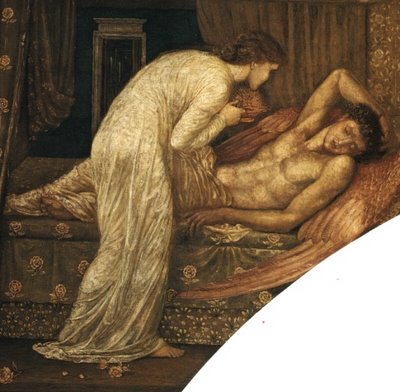

Despite the wonderful nights, Psyche grows bored during her long days with the invisible servants. She wants to tell her family she is OK, and even invite her sisters to visit. Little by little Cupid relents, but warns her that they may try to get her to see him; he cautions her to say nothing about her actual experience with him. The sisters do visit (6a, by Burne-Jones), borne from the mountain by Zephyr, and they size up her surroundings with all the skillful envy of Victorian gentlewomen.

The sisters worm out of Psyche the admission that she has never seen her husband. Her ignorance is their opportunity. They assure her that he is a dragon or a snake, as the oracle said, hardly the husband for a princess. She must kill him with a knife while he is asleep, and then they will find her a proper husband. She is to be like the modern Japanese-style Anime-Psyche painted by Carla Spandafora in 2003 (6b).

But really, shouldn’t she know whom she is sleeping with every night? Perhaps he isn’t even a he, as in Jacqueline Morreau’s 1986 take called “Cupid Disclosed” (6c).

Or maybe he is a gangster, or a closet homosexual. It’s important to know one’s lover.

And will he be aloof like that forever? This is the puer or puella aeternis, the eternal boy or girl who wishes to avoid entanglement and keep “free.” Moreover, Cupid is afraid his mother will find out. The puer’s imaginal connection to mother may be part of what holds him back; he has to remain true to her image of him, as he imagines it, regardless of dark facts. The sisters’ idea threatens his neat little holding of the contradictions. And so they leave, mission accomplished (6d, Burne-Jones).

Von Gierke’s corresponidng painting (6e), "Venus Selbstritt," Venus Looking at Herself, refers to Venus in its title. However for him Psyche doubles Venus. Occurring where it does in his series, I see the painting as applying more to Psyche:

There is a second painting of the same scene, having the same title, but with the model facing away from us. We shall look at that one in Chapter 7 (7d). I put it later because I identify it with Venus, depicting a parallel situation later, between Venus and her aunts, to the one now with Psyche and her sisters. Taking the reflections in 6e to be Psyche’s sisters, they are then mirrors of one’s unconscious soul, showing what is already there but not attended to by the subject. Again, the reflections in the painting are not exact images; they have their own reality and agenda--not that the subject would notice, so wrapped up is she in her stereotyped preoccupations.

Von Gierke puts a mysterious cup in his painting, a kind of jewelry box for her pearls and ribbon. In his close-up of the box (6f, "Stilleben," Still-life), the reflections in its surface are mysterious: lipstick, or perhaps a candle? But certainly phallic:

Seeing Cupid is the forbidden act. Christian commentators compared Psyche's transgression to Eve’s disobedience. In the Sophia story, what corresponds is her hybris, overweening pride, in trying to know the Godhead. In a Freudian reading, it is the forbidden viewing of the phallus.

And so Psyche carries out her plan, a lamp in one hand and a knife in the other. What she sees is not a monster but a beautiful young man whom she recognizes at once to be Cupid (6g, a 16th century fresco by Giulio Romano).

She is lost in wonder (6h-j, by Burne-Jones and Klinger).

She also feels regret and remorse; tears swell up and fall on Cupid’s body, along with drops of hot oil from the now-forgotten lamp (6k, by Lon Holdread, 2004). He awakens and feels the pain.

Immediately one hand slams down onto her hand holding the knife, while with the other he rips off his burning night shirt. The oil burns in back of him (6l, Jacqueline Morreau 1986-1993):

He flies away (6m, by Bartholomaeus Spangler, Prague, c. 1600). She grabs his right leg:

In medieval iconography, the right leg is intellect, the left is lust. Cupid is escaping from Psyche’s gaze, which threatened to reduce him to an object; ultimately it is the gaze of the Mother, a gaze that penetrates and kills like the knife.

Jung in Alchemical Studies saw an echo in the Gnostic tale of Sophia, Christ’s coming down to Sophia and then leaving without being known. In Jung’s anaysis, the man in Jung’s analysisis fleeing hot feminine emotions for cool detachment. It is another form of the puer’s escape from mother.

Psyche loses hold of the leg and falls to the ground. In some versions, Psyche just grasps in a futile gesture and sadly watches him go (6n, by Burne-Jones, and 6o, by Raphael).

In alchemy, this is the extractio (6p, Emblem 7 of the Rosarium), the spirit leaving the dead soul which has become pregnant.

The title attached to this emblem says this is the soul leaving the body—-thus the soul is represented as masculine. But where spirit is masculine, the picture could just as well be spirit leaving soul. Note that the body is now a hermaphrodite: reading the body as soul, that would mean that Psyche is not just herself anymore, but also has Cupid as part of her very being.

In Apuleius, Psyche does hold onto the leg briefly but then falls to the ground. Cupid turns and faces her angrily (6q, from a website about constructing video games; she is “Sister Psyche” as an action figure):

Cupid tells her that she listened to her foolish sisters against his warning and even sought to kill him at their instigation. So now Cupid must leave forever. Psyche despairs (6r, by Pietro Tenarani, 1816-17, and 6s, by Raphael, 1518).

Raphael’s sketch above is not explicitly of Psyche. Cavvicchioli, in her book on Cupid and Psyche, tells us that the identification is something generally agreed upon among art historians. The sketch was for a fresco never actually executed, although it is suggested in a fresco where Venus seems to be pointing to her.

Psyche’s pose in the sketch is that known as “Venus Pudica,” Venus Ashamed, or Modest. The term “Pudica” as an epithet of Venus is of interest to us. It has the same root as the Latin pudenda, genitalia. There was likewise a Venus Caelestis, Celestial Venus, and an Aphrodite Porne, Greek for Venus the Harlot. Similarly, the Gnostics called the lower Sophia, as opposed to the upper one, Sophia Prunicus, Sophia the Harlot. Thus Psyche is like the Gnostic Lower Sophia, expelled from the higher world for unlawfully trying to see the Father of All, separated from her divinity yet with a longing for the divine, thanks to the Christ’s brief visit to her in the Chaos.

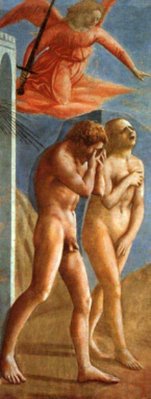

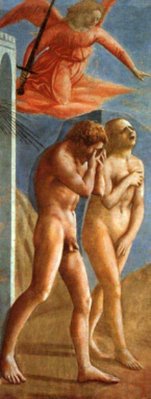

Renaissance Christian interpreters compared Psyche to Eve expelled from Eden. Such a comparison also seems implied in Raphael’s sketch, in which Psyche’s “Venus Pudica” pose is similar to a famous Eve done by the Florentine master Masaccio a hundred years earlier (6t).

Psyche still has her palace, but it is no longer what it was. In von Gierke’s image, she is perhaps starting to see the empty place for what it is, a house built of illusions, as one wall seems to merge with the landscape outside, and her image itself is only a painting hanging on another wall (6u, entitled “Interieur/Tuer,” Interior/Door)

The sisters worm out of Psyche the admission that she has never seen her husband. Her ignorance is their opportunity. They assure her that he is a dragon or a snake, as the oracle said, hardly the husband for a princess. She must kill him with a knife while he is asleep, and then they will find her a proper husband. She is to be like the modern Japanese-style Anime-Psyche painted by Carla Spandafora in 2003 (6b).

But really, shouldn’t she know whom she is sleeping with every night? Perhaps he isn’t even a he, as in Jacqueline Morreau’s 1986 take called “Cupid Disclosed” (6c).

Or maybe he is a gangster, or a closet homosexual. It’s important to know one’s lover.

And will he be aloof like that forever? This is the puer or puella aeternis, the eternal boy or girl who wishes to avoid entanglement and keep “free.” Moreover, Cupid is afraid his mother will find out. The puer’s imaginal connection to mother may be part of what holds him back; he has to remain true to her image of him, as he imagines it, regardless of dark facts. The sisters’ idea threatens his neat little holding of the contradictions. And so they leave, mission accomplished (6d, Burne-Jones).

Von Gierke’s corresponidng painting (6e), "Venus Selbstritt," Venus Looking at Herself, refers to Venus in its title. However for him Psyche doubles Venus. Occurring where it does in his series, I see the painting as applying more to Psyche:

There is a second painting of the same scene, having the same title, but with the model facing away from us. We shall look at that one in Chapter 7 (7d). I put it later because I identify it with Venus, depicting a parallel situation later, between Venus and her aunts, to the one now with Psyche and her sisters. Taking the reflections in 6e to be Psyche’s sisters, they are then mirrors of one’s unconscious soul, showing what is already there but not attended to by the subject. Again, the reflections in the painting are not exact images; they have their own reality and agenda--not that the subject would notice, so wrapped up is she in her stereotyped preoccupations.

Von Gierke puts a mysterious cup in his painting, a kind of jewelry box for her pearls and ribbon. In his close-up of the box (6f, "Stilleben," Still-life), the reflections in its surface are mysterious: lipstick, or perhaps a candle? But certainly phallic:

Seeing Cupid is the forbidden act. Christian commentators compared Psyche's transgression to Eve’s disobedience. In the Sophia story, what corresponds is her hybris, overweening pride, in trying to know the Godhead. In a Freudian reading, it is the forbidden viewing of the phallus.

And so Psyche carries out her plan, a lamp in one hand and a knife in the other. What she sees is not a monster but a beautiful young man whom she recognizes at once to be Cupid (6g, a 16th century fresco by Giulio Romano).

She is lost in wonder (6h-j, by Burne-Jones and Klinger).

She also feels regret and remorse; tears swell up and fall on Cupid’s body, along with drops of hot oil from the now-forgotten lamp (6k, by Lon Holdread, 2004). He awakens and feels the pain.

Immediately one hand slams down onto her hand holding the knife, while with the other he rips off his burning night shirt. The oil burns in back of him (6l, Jacqueline Morreau 1986-1993):

He flies away (6m, by Bartholomaeus Spangler, Prague, c. 1600). She grabs his right leg:

In medieval iconography, the right leg is intellect, the left is lust. Cupid is escaping from Psyche’s gaze, which threatened to reduce him to an object; ultimately it is the gaze of the Mother, a gaze that penetrates and kills like the knife.

Jung in Alchemical Studies saw an echo in the Gnostic tale of Sophia, Christ’s coming down to Sophia and then leaving without being known. In Jung’s anaysis, the man in Jung’s analysisis fleeing hot feminine emotions for cool detachment. It is another form of the puer’s escape from mother.

Psyche loses hold of the leg and falls to the ground. In some versions, Psyche just grasps in a futile gesture and sadly watches him go (6n, by Burne-Jones, and 6o, by Raphael).

In alchemy, this is the extractio (6p, Emblem 7 of the Rosarium), the spirit leaving the dead soul which has become pregnant.

The title attached to this emblem says this is the soul leaving the body—-thus the soul is represented as masculine. But where spirit is masculine, the picture could just as well be spirit leaving soul. Note that the body is now a hermaphrodite: reading the body as soul, that would mean that Psyche is not just herself anymore, but also has Cupid as part of her very being.

In Apuleius, Psyche does hold onto the leg briefly but then falls to the ground. Cupid turns and faces her angrily (6q, from a website about constructing video games; she is “Sister Psyche” as an action figure):

Cupid tells her that she listened to her foolish sisters against his warning and even sought to kill him at their instigation. So now Cupid must leave forever. Psyche despairs (6r, by Pietro Tenarani, 1816-17, and 6s, by Raphael, 1518).

Raphael’s sketch above is not explicitly of Psyche. Cavvicchioli, in her book on Cupid and Psyche, tells us that the identification is something generally agreed upon among art historians. The sketch was for a fresco never actually executed, although it is suggested in a fresco where Venus seems to be pointing to her.

Psyche’s pose in the sketch is that known as “Venus Pudica,” Venus Ashamed, or Modest. The term “Pudica” as an epithet of Venus is of interest to us. It has the same root as the Latin pudenda, genitalia. There was likewise a Venus Caelestis, Celestial Venus, and an Aphrodite Porne, Greek for Venus the Harlot. Similarly, the Gnostics called the lower Sophia, as opposed to the upper one, Sophia Prunicus, Sophia the Harlot. Thus Psyche is like the Gnostic Lower Sophia, expelled from the higher world for unlawfully trying to see the Father of All, separated from her divinity yet with a longing for the divine, thanks to the Christ’s brief visit to her in the Chaos.

Renaissance Christian interpreters compared Psyche to Eve expelled from Eden. Such a comparison also seems implied in Raphael’s sketch, in which Psyche’s “Venus Pudica” pose is similar to a famous Eve done by the Florentine master Masaccio a hundred years earlier (6t).

Psyche still has her palace, but it is no longer what it was. In von Gierke’s image, she is perhaps starting to see the empty place for what it is, a house built of illusions, as one wall seems to merge with the landscape outside, and her image itself is only a painting hanging on another wall (6u, entitled “Interieur/Tuer,” Interior/Door)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home