Chapter 2: The New Venus

In a 5th or 6th century version of the story, when Christianity was already the religion of the Roman Empire, Psyche was depicted as the daughter of the sun-god Apollo. Since Christ was seen as the new Apollo (his day of worship, after all is Sunday), Psyche thereby acquires a kind of divinity, like Christ and the various divine children of pagan Rome. On a 1490’s wedding chest from Florence, perhaps following this tradition, the sun shines behind the father at psyche’s conception (2a).

As she matures, she is adored not only as a divine child, but as "a second Venus."

Crowds come to worship her (2b, by Perin del Vaga, a pupil of Raphael's, for Pope Paul II). Meanwhile, Venus's own shrines are neglected.

It is as in the Gnostic myth, in which Sophia's nature divides in two, one half self-contained in the upper realm, and the other full of passionate longing in the Chaos below. This doubling symbolically represents two kinds of love, the divine and the human.

Psyche’s adoration takes away from Venus’s own. Venus is jealous and commands her son Cupid to use his arrows to make her fall in love with some fool and outcast from society, so she will be a laughing-stock (top right of 2b and all of 2c, by Raphael):

But Cupid, as the wedding chest tells it, falls in love with Psyche and wants her for himself (2d).

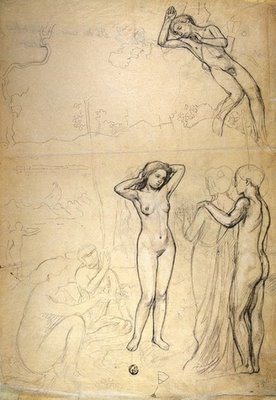

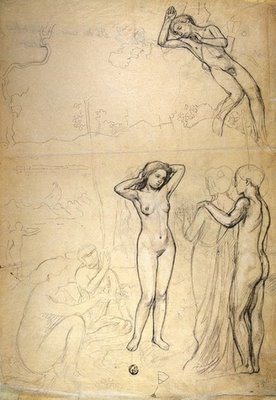

That Cupid falls in love with her is the artist’s interpretation, not in Apuleius’s tale. Perhaps it is only her body he wants, as beguilingly depicted in 2e, a sketch by the French artist Maurice Denis from around 1900.

In any case, Cupid will shoot his arrows nowhere near Psyche. Even before Cupid’s arrival, no one was proposing marriage to such a goddess-like being. Now it is certain that no flaming arrows will hit either her or those who gaze upon her.

In Wim Wender’s modern film fable "Wings of Desire" (2f, with actor Bruno Ganz), an angel looks down on our world as a bleak gray place filled with suffering:

Among the humans below he spies his own version of Psyche, a trapeze artist in a circus, who wears paper wings as part of her costume (2g, actress Solweig Dommartin with Wenders).

But the angel can woo her only if he becomes mortal by removing his wings, a step that is irreversible. In contrast to traditional views of redemption, this one is matter-centered.

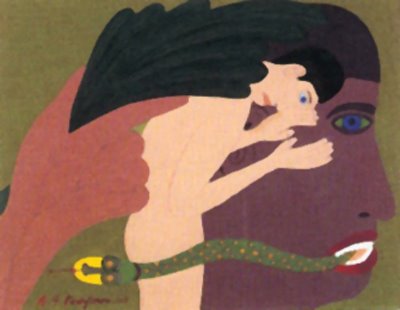

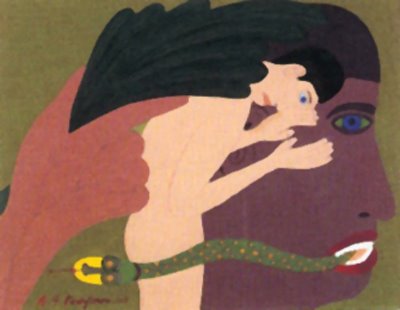

20th century art tends to follow this matter-centered approach. In a 1988 interpretation of the tale (2h, by an unschooled immigrant from Cyprus who worked as a guard in British museums and called himself “Perifimou,” Greek for “the famous one”).

The adored figure is now a projection of an inner figure, inside one’s head, so to speak. The inner figure is the Jungian anima, or soul, for a man, and animus, or spirit, for a woman. Actually, since the anima has an animus and vice versa, both genders have both inner figures. Perifimou’s figures are suitably androgenous.

In love, and desire generaly,, it as though one were looking at oneself in a kind of mirror, in love with one’s own unconscious image, like Narcissus in von Gierke’s 2005 depiction of the scene (2i), done for a 2005 exhibition in Zurich, Switzerland. It is perhaps no coincidence that Zurich is also the home of Jungian psychology.

Yet this image is also of a real human being, as for example the artist’s wife, looking at herself in a mirror tying a red ribbon in her hair (2j), the image von Gierke says on his website was the inspiration for his entire cycle of paintings:

You will notice that the image in the mirror is not a true reflection—-the head and the hand are not right. And a figure perhaps lurks behind the curtain.

As she matures, she is adored not only as a divine child, but as "a second Venus."

Crowds come to worship her (2b, by Perin del Vaga, a pupil of Raphael's, for Pope Paul II). Meanwhile, Venus's own shrines are neglected.

It is as in the Gnostic myth, in which Sophia's nature divides in two, one half self-contained in the upper realm, and the other full of passionate longing in the Chaos below. This doubling symbolically represents two kinds of love, the divine and the human.

Psyche’s adoration takes away from Venus’s own. Venus is jealous and commands her son Cupid to use his arrows to make her fall in love with some fool and outcast from society, so she will be a laughing-stock (top right of 2b and all of 2c, by Raphael):

But Cupid, as the wedding chest tells it, falls in love with Psyche and wants her for himself (2d).

That Cupid falls in love with her is the artist’s interpretation, not in Apuleius’s tale. Perhaps it is only her body he wants, as beguilingly depicted in 2e, a sketch by the French artist Maurice Denis from around 1900.

In any case, Cupid will shoot his arrows nowhere near Psyche. Even before Cupid’s arrival, no one was proposing marriage to such a goddess-like being. Now it is certain that no flaming arrows will hit either her or those who gaze upon her.

In Wim Wender’s modern film fable "Wings of Desire" (2f, with actor Bruno Ganz), an angel looks down on our world as a bleak gray place filled with suffering:

Among the humans below he spies his own version of Psyche, a trapeze artist in a circus, who wears paper wings as part of her costume (2g, actress Solweig Dommartin with Wenders).

But the angel can woo her only if he becomes mortal by removing his wings, a step that is irreversible. In contrast to traditional views of redemption, this one is matter-centered.

20th century art tends to follow this matter-centered approach. In a 1988 interpretation of the tale (2h, by an unschooled immigrant from Cyprus who worked as a guard in British museums and called himself “Perifimou,” Greek for “the famous one”).

The adored figure is now a projection of an inner figure, inside one’s head, so to speak. The inner figure is the Jungian anima, or soul, for a man, and animus, or spirit, for a woman. Actually, since the anima has an animus and vice versa, both genders have both inner figures. Perifimou’s figures are suitably androgenous.

In love, and desire generaly,, it as though one were looking at oneself in a kind of mirror, in love with one’s own unconscious image, like Narcissus in von Gierke’s 2005 depiction of the scene (2i), done for a 2005 exhibition in Zurich, Switzerland. It is perhaps no coincidence that Zurich is also the home of Jungian psychology.

Yet this image is also of a real human being, as for example the artist’s wife, looking at herself in a mirror tying a red ribbon in her hair (2j), the image von Gierke says on his website was the inspiration for his entire cycle of paintings:

You will notice that the image in the mirror is not a true reflection—-the head and the hand are not right. And a figure perhaps lurks behind the curtain.

1 Comments:

Very nice article! thanks!

Cupid At Psyche Buod

Post a Comment

<< Home