Chapter 1: Introduction

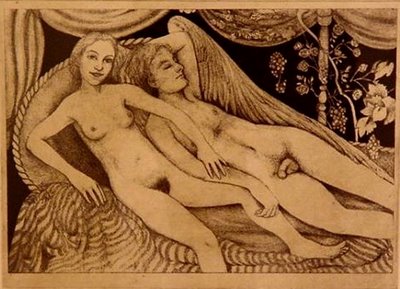

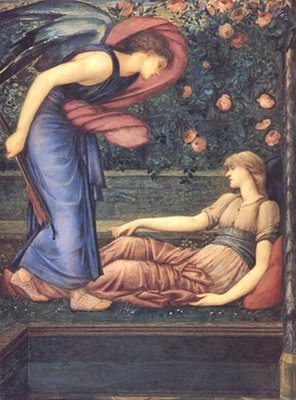

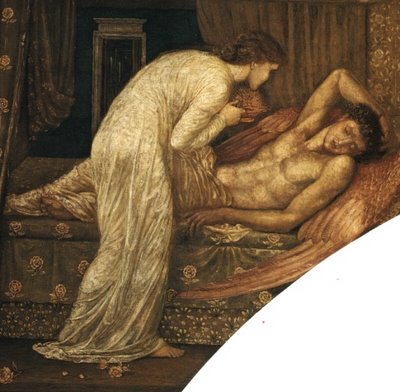

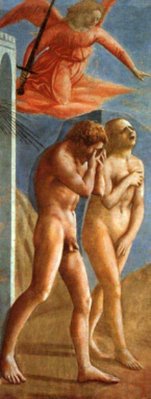

This blog is about the ancient story of Cupid and Psyche, historically considered to be a parable of the soul’s quest to attain unity with the spirit, through the purification of both. I will be telling the tale from a Jungian psychological perspective--but not, I think, from the same point of view as the major Jungian commentaries. I will be using artwork to add perspective, and also images from 16th and 17th century alchemical texts. The alchemists were on a similar quest, projected upon the chemical processes they were observing. And the story is a perennial favorite among artists, from the Renaissance to the present day.

The blog is the result of a slide show I presented at the Queen of Heaven Gnostic Church in Portland, Oregon, on April 30, 2006. For that audience, I drew parallels to the myth of Sophia in 2nd century Gnostic Christian writings, written at about the same time that the Cupid and Psyche myth was written in the form that we know it. I have kept these passages in the blog version. The Gnostic stories are visionary creation myths in the style of Plato's Timaeus, but within a Judeo-Christian context. Sophia, Greek for Wisdom, is a personification of the feminine aspect of God in late Judaic sacred writings. In the Gnostic texts her separation from the Godhead results in her striving for reunification, even at the risk of annihilation. She is the longing for the divine which can be satisfied only through arduous trials and with the aid of a Savior who must himself be prepared for the task. This is a theme that was already familiar in the Egyptian cult of Isis and Osiris and which priests of new cults were continuing in different forms

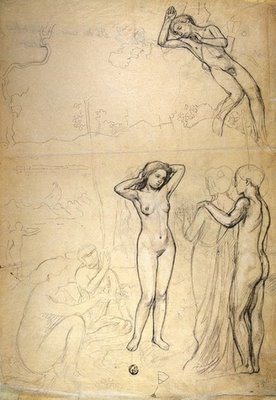

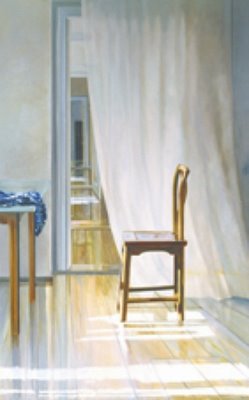

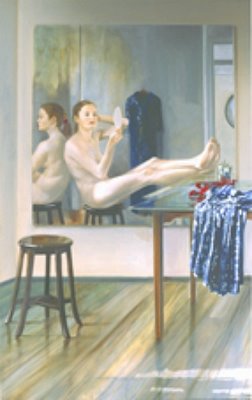

Many books and articles have been written about Psyche and Cupid. Two male Jungians, Erich Neumann and Robert Johnson, each wrote popular books applying the tale to the psychology of women. Marie-Louise von Franz, another Jungian, then wrote an analysis of the tale in terms of the unconscious feminine in men. For all three writers, apparently, the tale mainly applies to the other gender. From the vantage point of 35 years or more, all three books seem riddled with outdated gender stereotypes. Many of the artworks, however, remain as fresh as when they were painted, even though they take a variety of perspectives on the tale.

The art, in fact, provides a way not only to deepen one’s experience of the tale but also to make it one’s own in the same language used by the unconscious, as expressed in dreams, for example. I encourage the viewer not to see the art as mere supplements to the words, but as roads in their own right toward making Psyche’s journey one’s own. In support of that end, I have tried to keep my commentary to a minimum.

Some of the images on this blog, those that wider than they are high, can be made larger by clicking on them. Then use your browser (the green back arrow at the top left of your screen)to get back to the main text. If the reloading time is too long, you can cut it down by reading the blog chapter by chapter, clicking on the chapter headings to the right of this Introduction.

The tale of Cupid and Psyche was originally a Greek folk tale. There are surviving statues of the pair from long before it came to be written down. Its folk status is attested by its recurrence in fairy tales such as Cinderella. In ancient times Cupid was also shown as guiding Psyche: as Plato taught, the guide of the soul in its spiritual quest is love.

Psyche is the Greek word for both soul and a kind of moth--hence Psyche’s small wings in slide 1a, a statue from Roman times.

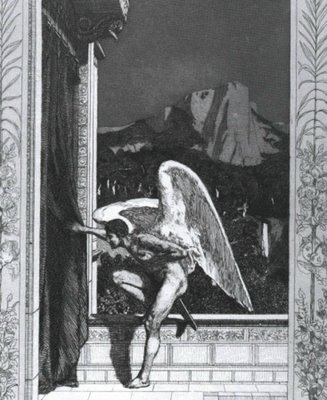

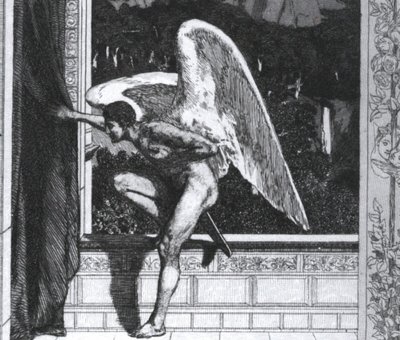

In slide 1b, Cupid is shown riding a moth. He, too, has wings.

The moth is particularly appropriate because it is known for seeking the light. Psyche's search for love is on another level the search of the soul for illumination from a divine source .

Cupid, also called Amor or Eros, was of course the god of love, son of Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, and of Vulcan, blacksmith and all-round artisan for the gods.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the tale survived in only one verison, that by Apuleius, a Roman who lived in what is now Tunisia, in the same 2nd century milieu that produced the Gnostics. It occurs in the middle of a long novel called The Metamorphoses, or more popularly, The Golden Ass. The novel's protagonist is a young man who turns into a donkey until liberated by the Goddess Isis. Like his contemporary Plutarch, Apuleius used the Egyptian cult of Isis and Osiris at the end of the novel to expound his views. Both writers took a very positive view of the divine feminine.

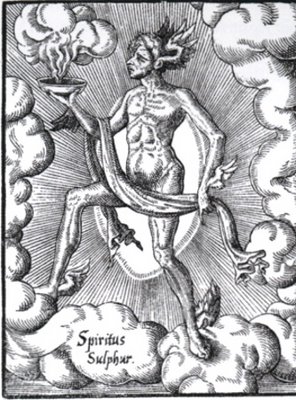

Jung saw alchemical and Gnostic aspects to the tale, as well as the psychological, i.e.soul, aspects picked up on by Neumann and von Franz. For Jung the tale is about the transformation of body and spirit as well as of soul. In alchemy, spirit was sometimes “Sulphurous Spirit” (1c, from the Quinta Essentia of 1599) and given wings like Cupid, but more in the way that the god Mercury had wings, in his cap and shoes.

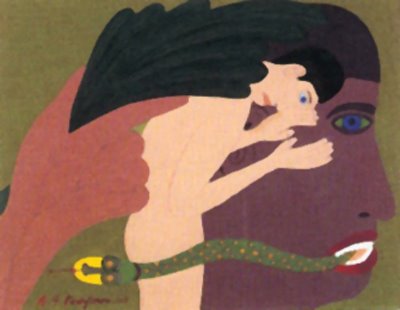

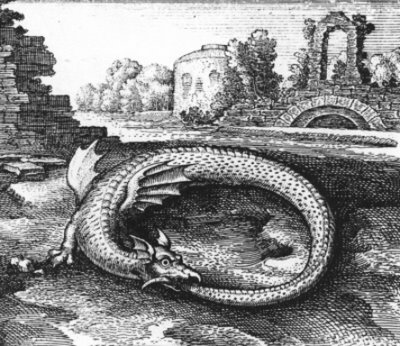

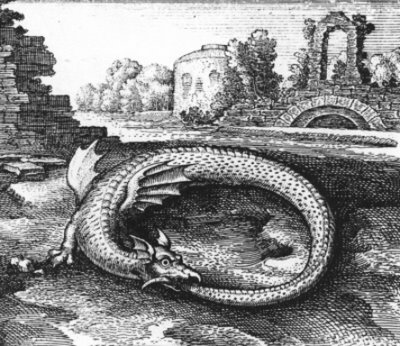

The alchemists characterized Sulphur as a kind of demonic power in nature, usually up to no good, even a kind of dragon biting its tale (1d, from the Atalanta Fugiens of 1618); yet when tamed or transmuted it can work great good. This characterization is more appropriate to Cupid than to Mercury, when you remember that sexual love was considered a curse rather than a blessing.

Soul, on the other hand was the Anima Mercury, “Mercurial soul” (1e), depicted as a woman with rays radiating out from her womb. (Images 1c and 1e both come from a 17th century edition of the Quinta Essentia of 1579).

As we shall see later, however, sometimes the alchemists imagined soul as masculine and spirit feminine.

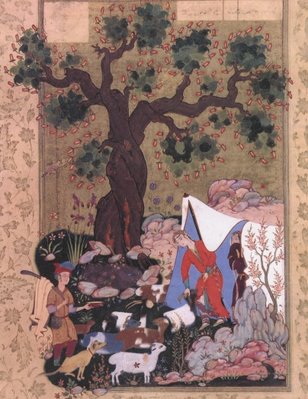

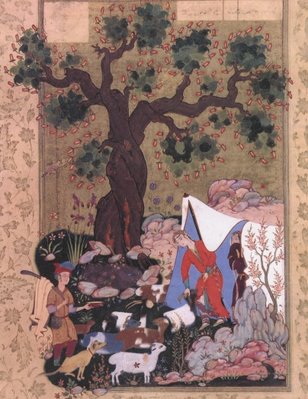

In Medieval Islam, corresponding to Psyche and Cupid, there was the tale of Layla and Majnun (1f): Majnun after may trials in the desert disguises himself in a sheepskin so as to elude Layla’s guards.

Here the roles are the reverse of those of Cupid and Psyche, where it is Psyche who has the trials so as to be with Cupid. Another example is Beatrice guiding Dante in the Divine Comedy.

The blog is the result of a slide show I presented at the Queen of Heaven Gnostic Church in Portland, Oregon, on April 30, 2006. For that audience, I drew parallels to the myth of Sophia in 2nd century Gnostic Christian writings, written at about the same time that the Cupid and Psyche myth was written in the form that we know it. I have kept these passages in the blog version. The Gnostic stories are visionary creation myths in the style of Plato's Timaeus, but within a Judeo-Christian context. Sophia, Greek for Wisdom, is a personification of the feminine aspect of God in late Judaic sacred writings. In the Gnostic texts her separation from the Godhead results in her striving for reunification, even at the risk of annihilation. She is the longing for the divine which can be satisfied only through arduous trials and with the aid of a Savior who must himself be prepared for the task. This is a theme that was already familiar in the Egyptian cult of Isis and Osiris and which priests of new cults were continuing in different forms

Many books and articles have been written about Psyche and Cupid. Two male Jungians, Erich Neumann and Robert Johnson, each wrote popular books applying the tale to the psychology of women. Marie-Louise von Franz, another Jungian, then wrote an analysis of the tale in terms of the unconscious feminine in men. For all three writers, apparently, the tale mainly applies to the other gender. From the vantage point of 35 years or more, all three books seem riddled with outdated gender stereotypes. Many of the artworks, however, remain as fresh as when they were painted, even though they take a variety of perspectives on the tale.

The art, in fact, provides a way not only to deepen one’s experience of the tale but also to make it one’s own in the same language used by the unconscious, as expressed in dreams, for example. I encourage the viewer not to see the art as mere supplements to the words, but as roads in their own right toward making Psyche’s journey one’s own. In support of that end, I have tried to keep my commentary to a minimum.

Some of the images on this blog, those that wider than they are high, can be made larger by clicking on them. Then use your browser (the green back arrow at the top left of your screen)to get back to the main text. If the reloading time is too long, you can cut it down by reading the blog chapter by chapter, clicking on the chapter headings to the right of this Introduction.

The tale of Cupid and Psyche was originally a Greek folk tale. There are surviving statues of the pair from long before it came to be written down. Its folk status is attested by its recurrence in fairy tales such as Cinderella. In ancient times Cupid was also shown as guiding Psyche: as Plato taught, the guide of the soul in its spiritual quest is love.

Psyche is the Greek word for both soul and a kind of moth--hence Psyche’s small wings in slide 1a, a statue from Roman times.

In slide 1b, Cupid is shown riding a moth. He, too, has wings.

The moth is particularly appropriate because it is known for seeking the light. Psyche's search for love is on another level the search of the soul for illumination from a divine source .

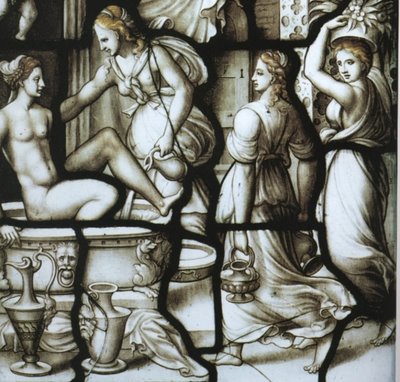

Cupid, also called Amor or Eros, was of course the god of love, son of Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, and of Vulcan, blacksmith and all-round artisan for the gods.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the tale survived in only one verison, that by Apuleius, a Roman who lived in what is now Tunisia, in the same 2nd century milieu that produced the Gnostics. It occurs in the middle of a long novel called The Metamorphoses, or more popularly, The Golden Ass. The novel's protagonist is a young man who turns into a donkey until liberated by the Goddess Isis. Like his contemporary Plutarch, Apuleius used the Egyptian cult of Isis and Osiris at the end of the novel to expound his views. Both writers took a very positive view of the divine feminine.

Jung saw alchemical and Gnostic aspects to the tale, as well as the psychological, i.e.soul, aspects picked up on by Neumann and von Franz. For Jung the tale is about the transformation of body and spirit as well as of soul. In alchemy, spirit was sometimes “Sulphurous Spirit” (1c, from the Quinta Essentia of 1599) and given wings like Cupid, but more in the way that the god Mercury had wings, in his cap and shoes.

The alchemists characterized Sulphur as a kind of demonic power in nature, usually up to no good, even a kind of dragon biting its tale (1d, from the Atalanta Fugiens of 1618); yet when tamed or transmuted it can work great good. This characterization is more appropriate to Cupid than to Mercury, when you remember that sexual love was considered a curse rather than a blessing.

Soul, on the other hand was the Anima Mercury, “Mercurial soul” (1e), depicted as a woman with rays radiating out from her womb. (Images 1c and 1e both come from a 17th century edition of the Quinta Essentia of 1579).

As we shall see later, however, sometimes the alchemists imagined soul as masculine and spirit feminine.

In Medieval Islam, corresponding to Psyche and Cupid, there was the tale of Layla and Majnun (1f): Majnun after may trials in the desert disguises himself in a sheepskin so as to elude Layla’s guards.

Here the roles are the reverse of those of Cupid and Psyche, where it is Psyche who has the trials so as to be with Cupid. Another example is Beatrice guiding Dante in the Divine Comedy.